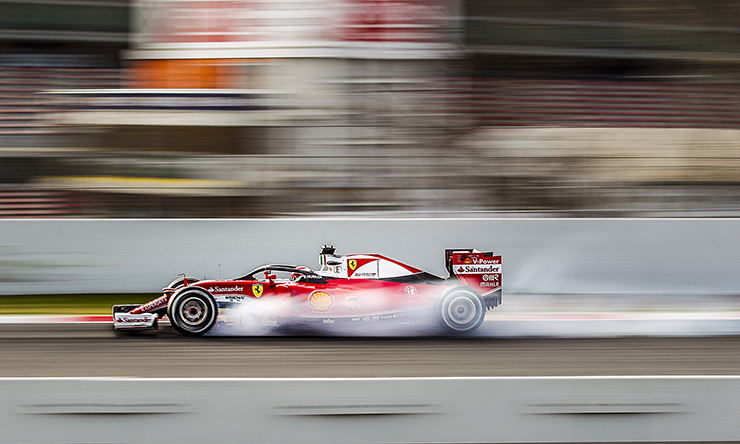

Photos via James Moy

With respect to motorsports and sporting competitions, the off-season is a term ordinarily associated with the time of the year free from the competition of the regular season. It’s a chance for professional teams and athletes to partake in a normal schedule of free time and uninhibited vacations – that is, unless one is part of a Formula One team. If this is the case, the off-season is merely the scramble to put months – or years – worth of research into practice, and bring this research to fruition before the start of the racing season in late March. Whether it’s adapting to ever-changing regulations, or merely trying to find a loophole in the existing rulebook to gain a performance advantage, the off-season is a mad dash for everyone associated with the sport leading into the upcoming competitive term. The benefits of this seemingly endless activity are evidenced during the official preseason testing, this year hosted by the Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya in Barcelona, Spain.

Formula One (F1) is, without question, the pinnacle of motorsport competition on the planet. While recent years have birthed a new breed of calculated technical racecars differing in excitement from the brute force machines of yesteryear, there is no argument that its combination of constant ground-breaking technology and slipstream aerodynamic designs combined with the demanding racetrack schedule keeps the race series firmly placed at the peak of automotive competition.

The elite teams that are fortunate enough to compete – and have top-flight financial backing – in this upper echelon of auto racing must abide by a very strict yet fluid set of rules. Even if a team figures out a way around a restriction in the regulations, the change must first be passed by the FIA, the sport’s governing body. Short for Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile, this group is responsible for keeping one of the most lucrative professional sports on a level (ish) playing field. Also tasked with keeping F1’s participants safe, the FIA is constantly adjusting spoiler and tire size, engine power, engine size, and other parameters in an effort to manage the world’s most advanced racecars and maintain relative parity between the competitors. The byproducts of these efforts are shown through the teams’ undying innovative efforts and the performance concepts delivered to the racing grid; in many scenarios these ‘reinvent the wheel’, so to speak, as the teams continue to display the progressive thinking synonymous with Formula One racing.

As an example, back in the 2010 season the FIA regulations dictated that all the new cars would be equipped with much smaller rear wings, thus decreasing rear airflow and downforce; this in turn provides much less grip to the rear wheels to slow down the speeds around corners. As a loophole, the Red Bull Racing team routed their engine’s exhaust to flow through and overtop of the rear diffuser, named the exhaust blown diffuser (EBD). These created more airflow and more downforce regardless of the smaller rear wing mounted overtop. This proved to be an incredibly valuable breakthrough as Red Bull Racing’s cars were unstoppable – in particular, the efforts of 2010’s World Champion Sebastian Vettel, who stood on the podium in 11 out of 19 races that season. The EBD has since been outlawed due to the overwhelming advantage it provides on the track.

Today, the same restrictions are in place to limit the speed of the cars, which has the effect of working to further push the sport into scientific and technological areas previously unknown. Illustrated here by Lewis Hamilton in the Mercedes AMG F1 W07 Hybrid, a rulebook change for 2016 involves the turbocharged engine’s exhaust systems. They must have only a single turbine tailpipe exit and either one or two wastegate tailpipe exits which all must be rearward facing. This rule has the effect of eliminating the ability for any of the teams to take advantage of rerouting their exhaust for added downforce – for now.

Gene Haas, the owner of Haas Automation – a designer and manufacturer of precision machining tools like CNC and turning machines – is responsible for the first American-led Formula One team in competition since 1986, the Haas F1 team.

Among the other changes for 2016 is a shorter preseason testing schedule than years past, as each team will now be given eight days of testing in preparation for the new season, rather than the 12 available previously. This truncated testing calendar will prove to be a large obstacle for new teams – like Haas F1 – to work out the kinks in their new system. Haas signed up French driver Romain Grosjean and Mexican driver Esteban Gutierrez to pilot the Haas-Ferrari VF-16 car. Although both drivers are reasonably new to the sport, they will offer insight into creating a successful team by relating issues to their past experiences with other teams and forms of racing.

The hottest topic of discussion during testing was the FIA’s decision to start looking into cockpit safety more genuinely. In October of 2014, the Formula One series suffered its first race-related driver fatality since the 1994 season. Jules Bianchi, a 25 year old French driver for the Marussia Formula One team, succumbed to injuries associated with an incident when his car collided with a crane being operated as part of the safety vehicle machinery. While the crane was removing another car that had crashed in the same corner a lap prior, Bianchi’s car lost grip in the wet track conditions and slid off-track, where it drove underneath the crane. This forced his helmet directly into the equipment and ultimately took his life. After the incident, it was determined that the driver’s open cockpits would need to be revised to prevent any further incidents. Although the only official rule change for this year requires the configuration of the bodywork surrounding the driver’s head in the cockpit to be raised an additional 20mm, the push towards closed-cockpit Formula One cars is closer than ever. In order to protect the sport’s integrity and the history of open-cockpit cars, teams like Scuderia Ferrari have already begun working on their own open solution. Enter the company’s halo concept, which is a rigid assembly of carbon fiber built to provide three structural support points and protection overtop of the driver’s only vulnerable body part – their head. Red Bull Racing is said to be working on an alternative concept utilizing a large windscreen to shield the driver without causing the vision issues associated with Ferrari’s halo design.

The aerodynamic attributes of a Formula One car – the wings that determine how slippery the car is through the air – are continually changing throughout the season, especially from track to track, but most major changes make their debut during the unveiling of the car after the off-season full of research and development efforts. Each team has their own individual procedure for presenting their new competitive racecar to the world; after its release to the media, most cars will remain behind closed doors. Similar to the secretive underground nature of a closely guarded military secret, these cars are kept away from prying eyes, in order to prevent any other teams from noticing a game-changing alteration or gaining an advantage before the season starts. Why is the airflow so important for these cars? Picture the wings of an airplane; similar to how an airplane is designed with every feature tuned to help keep it aloft, a Formula One car is designed to stay planted on the ground to maximize the grip available to the tires, which has the intended effect of dropping vital seconds off lap times.

Due to a regulation restricting the use of full scale wind tunnel testing to visualize the airflow over the chassis, teams have found other ways to generate the information they need when designing these bespoke cars to cut through the air. One method is aero-mapping, illustrated here by Valtteri Bottas in the Williams FW38 (top) and Sebastian Vettel in the Ferrari SF16-H (bottom). This technique involves mounting these custom sensor grids to the car, usually just behind the wheels or along body panels. These grids – called aero rakes – are riddled with electronic sensors to translate the car’s behavior on the track into numerical data, which can subsequently be digested by team engineers to determine the car’s characteristics. Some of the ultra-advanced measurements these rakes record are air speed, angle flow, pressure, and even varying temperature. Using this recorded data, the teams are able to make adjustments on a digital simulation of the car to determine how the wings should work before ever physically changing the car, dramatically shortening the development cycle and providing cost efficiencies

Among other obscure methods for obtaining data, the teams use a highly fluorescent paint sprayed across components or panels of a car like the green, red, and light blue covering the usually black-chrome McLaren-Honda MP4/31. This fluorescent airflow visualization paint or flow-vis is used to confirm that the physical airflow across the body of the car is identical to the simulated airflow from the digital versions of the car displayed throughout numerous test programs. The paint is mixed to remain wet until the desired speed is achieved, forcing the paint particles to spread across the body as wind forces them to dry. The result is a clear physical representation of airflow; one of the drawbacks of this process is the effect it has of revealing the data to anyone who can see the car during the test laps. Any faults in the flow – or any aerodynamic secrets discovered – are completely visible to any of the teams present at the testing session.

With only eight days of testing in Barcelona, the teams try to squeeze every ounce of testing time out on track. Some teams even found themselves idle at the end of pit road at 9 a.m. sharp, waiting for the green flags to fly and the track session to commence. The newcomers – Haas F1 – were one of those teams, though their eagerness to begin testing couldn’t protect them from the hiccups of the new chassis (and race program). They struggled to collectively log 474 laps between their two cars over the eight-day span, the lowest of any team at the testing. Though the American team’s fastest lap of 1:25.255 by Romain Grosjean is less than 3 seconds off the pace of the fastest car of the week, the Scuderia Ferrari of Sebastian Vettel’s 1:22.765, that 3 seconds per lap is closer to an eternity in Formula One. The Haas-Ferrari VF-16 car is definitely in for a bumpy ride this season.

Over the past two seasons, Mercedes’ dominance over the rest of the field has been demonstrated during each race. Assuming the cars are being pushed to their fullest extent throughout this testing, the Mercedes AMG F1 W07 Hybrid car may have a close fight on their hands, as they finished the week with a best lap time of 1:23.022 from driver Nico Rosberg, a mere 0.257 seconds off the pace of the Scuderia Ferrari SF16-H car. We look forward to round one of the season, the Australian Grand Prix at Albert Park in Melbourne, Australia in two weeks’ time – March 17-20, 2016.